by Preston Cooper

A whistleblower lawsuit filed last month alleges that Rutgers University’s business school artificially boosted its rankings by using a temp agency to hire MBA graduates and place them into “sham positions at the university itself,” according to NJ.com, which first reported the news. Though shocking, the scandal is the natural result of the incentives the federal government has set up for schools through uncapped student loan subsidies for graduate programs.

Rutgers has denied the charges. But the allegations are credible when considering the source: the lawsuit was filed by Deidre White, the human resources manager at Rutgers’ business school. Days later, a separate class-action lawsuit was filed by one of Rutgers’ MBA students.

Last year Rutgers was ranked first among public business schools in the northeast by Bloomberg Businessweek. One wonders how many students, hoping for a degree that would boost their employability, may have been deceived by that rosy statistic.

The scandal follows similar incidents at other universities. The University of Southern California withdrew from the U.S. News & World Report graduate education school rankings due to “inaccuracies” in its reported data stretching back for years. And earlier this year, the dean of Temple University’s business school was sentenced to more than a year in prison for submitting false data to U.S. News.

Why would university officials risk prison time to manipulate their rankings? The answer is that graduate degrees—especially master’s degrees—are increasingly becoming a cash cow for universities. Though federal loans to dependent undergraduate students are capped at $31,000, loans to graduate students are effectively unlimited.

Many schools have vastly expanded their graduate school offerings to soak up this stream of cash. The number of master’s degrees conferred annually has risen 41% since 2006, when unlimited loans for graduate students were introduced. Over the past decade, universities have added more than 9,000 new master’s degree programs.

The master’s-degree bonanza shows no sign of tapering off. While the number of students pursuing higher education has dropped 6% overall since the beginning of the pandemic, enrollment in master’s degree programs has moved in the opposite direction, surging by nearly 6%.

Predictably, this has led to a surge in graduate student debt. In 2019-20, 43% of all federal student loans issued were for graduate education, up from 33% at the beginning of the decade. Rutgers itself gets over half of its federal student loan funding from graduate programs. For many prominent universities, undergraduate education is old news—graduate programs are where the real money is.

Unfortunately, much of this federal largesse finances programs of questionable financial value. According to my estimates of return on investment, 40% of master’s degrees do not provide their students with an increase in earnings large enough to justify their costs. Among MBAs and other business-related master’s degrees, the share of nonperforming programs rises to 62%. Perhaps that reality is a reason that so many graduate schools feel the need to fudge rankings data.

Many graduate borrowers will strain under the weight of debt that the federal government so freely gave out. But taxpayers will pick up a large share of the burden as well. Most graduate borrowers are eligible for income-based repayment programs which limit their monthly payments and grant loan cancelations after a set period of time. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that more than half of graduate loans issued in 2022 and repaid on income-based plans will eventually be discharged.

The student loan payment pause has also transferred many of the costs of graduate school from borrowers to taxpayers. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that the average master’s degree holder has already received over $13,000 of effective loan forgiveness through canceled interest payments and excess inflation during the pause. These factors, plus the possibility of additional loan forgiveness in the future, allow universities to hint that students might not have to pay the full cost of their education—and makes it easier to sell them on expensive master’s degrees.

The Education Department has the tools to put a stop to this racket. A regulation known as borrower defense to repayment allows students defrauded by their institutions to have their federal student loans canceled; the institution must make taxpayers whole in the event of a successful loan discharge. Initially developed by the Obama administration, the rule was aimed at for-profit colleges, but there’s no reason it couldn’t be used against a public flagship university like Rutgers. If the Education Department forced a school with provably falsified rankings data to pay off the loans of defrauded students, it would send a firm signal that this sort of behavior will not be tolerated.

But borrower defense to repayment isn’t enough. There are plenty of federally funded master’s degree programs where institutions are not guilty of fraud, but outcomes are abysmal nonetheless. Therefore, it is also necessary for Congress to remove the incentive for universities to market bad master’s degrees in the first place: their unlimited federal funding.

The prevalence of master’s degrees that offer little to no return on investment can be chalked up to uncapped federal student loans, which are handed out in an undiscriminating fashion, and the repayment regime that forces taxpayers to pick up the tab for unpaid loans. Universities push low-quality master’s degrees to capture the federal dollars, while students are willing to borrow thanks to the federal government’s implicit stamp of approval. End federal loans for graduate school, and most low-quality master’s degrees will vanish.

Private lenders would be able to meet demand for the financing of quality graduate degrees, such as medicine. Reliable financial returns for these degrees mean that private lenders will jump at the chance to lend to medical students attending reputable institutions, but will be far more hesitant to pony up $180,000 for a master’s degree in film. A thriving private market for graduate student loans existed before Congress uncapped federal loans in 2006. There is no need for a federal graduate loan program when the private sector can adequately fill the role.

The brewing scandal at Rutgers is a sign that many universities will do anything for a piece of the federal government’s unlimited graduate loan offerings. By ending federal loan subsidies for graduate programs, Congress can fix the bad incentives that led to this mess, protect students from low-quality master’s degrees, and save taxpayers a heap of money along the way.

– – –

Preston Cooper is a research fellow in higher education at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

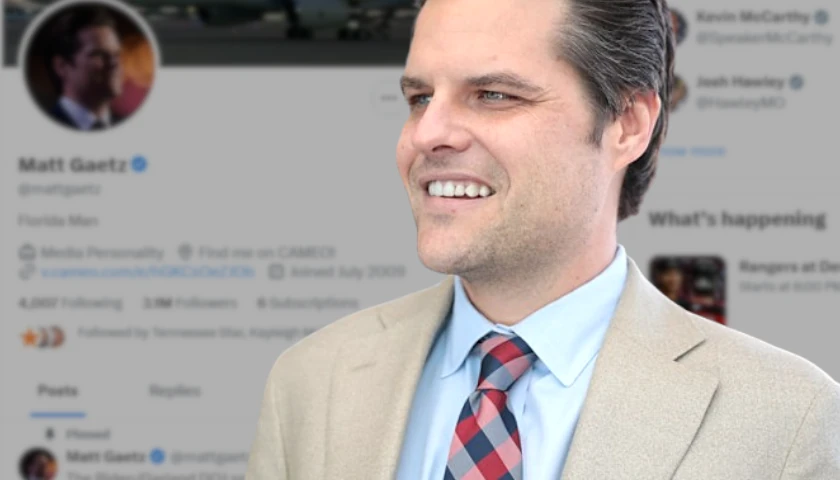

Photo “Rutgers University Business School” by Rutgers University Business School.