by Vincent McCaffrey

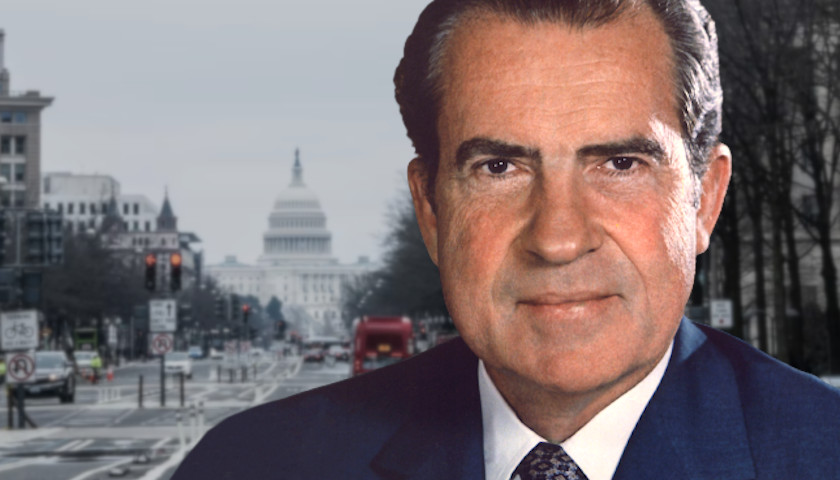

The 1968 presidential election was my first. I voted for the erstwhile Republican, Richard M. Nixon. And because I wrote a college paper about my decision at the time, causing complete consternation for that professor, I still have a clear idea of why I did it. The choice was between Nixon and Democrat Hubert H. Humphrey. The other candidate on the ballot, George C. Wallace, was a populist with proven racist views and unpalatable.

I say erstwhile Republican because even though Nixon campaigned on what was then a relatively consistent Republican menu of positions—pro-business, favoring a strong dollar and law and order—he quickly abandoned most of these and became a tool of the military-industrial complex his old boss, Dwight Eisenhower, had warned against.

Being 21 years-old at the time, a compelling argument to me was Nixon’s pledge to end the draft. The undercurrent to this, of course, was the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, which was then raging, and deep in the midst of killing nearly 60,000 young American men and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese for dubious reasons.

It’s worth recalling that the mainstream press, led then by the New York Times, Washington Post, and the three television networks (there were still only three!) were vociferously anti-Nixon. Had their favorite Republican, Nelson Rockefeller, made it through the primaries, the imbalance might have been less severe. But as it was, it was unmistakable even to the political novice.

Hubert Humphrey was given a pass. His solutions to the nation’s problems were mostly unintelligible slogans and contradictory when they could be understood at all. Essentially, he was against racism and for spending more tax money on poverty—a process that was already proving disastrous.

The better Democrat (i.e., socialist) would have been Eugene McCarthy, and though I was already more libertarian in direction, I might have voted for him instead had he been on the ticket, simply to go against the powers that be. But those same powers had already eliminated him in the primaries.

Machiavelli would have been dumbfounded by the machinations of the time. The internecine struggles, though obvious on the surface with the assassinations of both John and Robert Kennedy as well as Martin Luther King, were a morass of interests, each with their own objectives. As complex a character as Nixon was, and despite his attempts to play the game by placating the military, devaluing the currency in a Keynesian attempt to reduce the national debt, and increasing the size of government with new sinecures of power, he was no match for it. In the end, and despite his relative popularity for talking a good game, he was brought down and replaced by ciphers.

Since that time, to use another historical reference, the workings of the deep state have become Byzantine—right down to the use of ruthless armies of eunuchs.

But somehow America persisted. Blessed with a natural wealth of resources and a diverse population with similar Judeo-Christian core values, for a long time we were indomitable. But note the past tense.

In retrospect, from the perspective of 2022, it is difficult to understand just how we made it through this far. The political corruption alone seems impossible. But the real conundrum, even if you think you have a clue to all the significant forces that stand against us, is to grasp enough of it to imagine a way out of this labyrinth of conflicting interests, none of which is populated with people who seem to bear us good will. You can’t just throw up your hands. It will trample you. And remember to keep your arms out so they can’t get the straight jacket on.

Back in the day, “Nixonian” became a word. It had no particular meaning, other than to indicate something complex and perhaps convoluted and associated with the man. It was understood to be negative, though just how so was not made clear. Fifty years after Richard Nixon’s great landslide victory we have a clearer idea about the political interests that stood against him, and, as detailed by recent historians of the period, they were formidable.

The Democrats, of course, relished the chance to get back at “Tricky Dick,” the anticommunist who had managed to foil them repeatedly since 1948 simply by refusing to die. Worse, through his overtures to China, Nixon was stealing a page from their own book.

It is clear that the CIA was involved in Watergate, just as they were, not coincidentally, in bringing down Trump. Hoover’s FBI, already compromised, chose sides. The military sided with the keepers of the purse in Congress. The Republican Party, feeling its oats, but divided between liberals and conservatives, abandoned Nixon for not taking orders—or the right orders—or for not simply letting them have their way. Nixon’s own White House was divided politically and further compromised by the unappointed bureaucracy, those who always favor the long term establishment.

The Watergate hearings, the sort of show trial Washington had not enjoyed since Joe McCarthy, displayed the senatorial grandstanding and self-righteous posturing of a gaggle of Captain Louis Renaults, all shocked at the gambling going on.

But even with all this against Nixon, and very likely much more given the various Marxist interests and Soviet sympathies, what we see today is exponentially more dangerous. The giant AT&T of 1972 was nothing compared to tech monsters such as Google, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft that control our communications today. The Cold War threat from the Soviet Union, in other words, has metastasized into a threat from multiple evil powers—and all that is before we even include China—all with far greater reach. International corporate control over every essential aspect of our lives, from food and water to fuel and clothing, has placed our most basic security in the hands of strangers who put their own interests first.

The elections of 1972, when voting was in person and done by paper ballot, still had various incidents of chicanery by the usual suspects in Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, etc., but then the national vote was overwhelming. Today, with fraud condoned in states as diverse as New Mexico, Wisconsin, and Georgia, “overwhelming” is simply not enough.

What is to be done? A “nation of immigrants” is being overwhelmed by illegal immigrants, most of whom do not have similar values. Since 1972, the educational system has processed two generations of graduates who have little or no interest in the principles for which we once stood. A fifth column of so-called journalists, cured in the bile of Watergate frauds like Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, all too willing to sell their souls to get ahead while believing everyone is as corrupt as they are, now only report the news that “fits” the narrative.

In retrospect, it may be too easy to see the parallels between then and now. It is always best to recognize the differences in human beings as much as the similarities. Machines may duplicate, people not so well. For instance, I think Nixon’s great strategic error in the game that he played, apart from any principles he might have had, was to choose Spiro Agnew as his vice president. This single act opened him to the jackals he had fended off for decades. If he had chosen a more moderate political manager, one who “knew the ropes,” his enemies would have had to abide. But then, of course, that is what President Trump did in choosing Pence when he needed a Patton. And as they say, so it goes.

This may not be our “darkest hour.” That may still be ahead. But given the stakes, we had better act as if it were.

– – –

Vincent McCaffrey is a novelist and bookseller. Visit his website at www.vincentmccaffrey.com.