by Natalia Mittelstadt

Counties across the U.S. are switching to hand-counting election ballots instead of using electronic tabulation machines over concerns about the accuracy and security of the devices.

At the forefront of the transition is election integrity advocate Linda Rantz, who says her model, now being used in a Missouri county, is less expensive than critics continue to say it is.

While the security of the country’s election system has always been a concern, the matter burst into the public eye in the 2020 presidential election, amid the concerns of then-President Trump and others about the reliability and transparency of voting machines.

Early this year, the board of supervisors in California’s Shasta County, with over 110,000 registered voters, decided to move to hand-counting for all of its elections, after voting in January to terminate its contract with Dominion Voting Systems over concerns about its voting machines.

“There is a great sense they would like to return to something simpler and safer and more secure from outside hacking,” said county Board of Supervisors Chairman Patrick Jones.

Dominion in more recent months became the center of attention over the security of its and similar voting machines.

In April, the Fox News Channel agreed to pay Dominion $787.5 million in a defamation lawsuit in connection with the cable network airing claims the company “committed election fraud by rigging the 2020 presidential election” and that its software and algorithms “manipulated vote counts” in the election.

According to Shasta County’s estimate, shifting to hand-counting would increase the net county cost from $2.94 million to $3.14 million.

And county Registrar of Voters Cathy Darling Allen, a Democrat, says 1,300 additional workers also would be needed.

Allen also recently said she has concerns about switching to hand-counting because of the cost and “issues regarding accuracy.”

“We use hand counting at scale across the United States to verify election returns and audit mechanical election processes, and it works really well for that – in small batches,” she said. “But humans are not great at doing repetitive tasks over and over for long periods of time. Machines are.”

Meanwhile, Missouri’s Osage County transitioned to hand-counting ballots in its April election, and the state’s Worth County has been hand-counting elections for the past decade.

Byron Keelin, president of the Freedom Principle MO, told Just the News on Thursday that Missouri allows counties to hand count ballots for elections but it is not a requirement.

A Senate bill in the state’s most recent legislative session would have required counties to eliminate all voting machines, ballot tabulation machines, and electronic poll-books. However, the measure died in committee when the session ended.

Keelin says his group will work to have the bill reintroduced when the next legislative session begins in January.

“There are false narratives that hand-counting will cost more money and more time,” he recently told the St. Louis Record. “If you look at what happened in Osage, they basically counted all of the votes in the county and reported the results of the election at the same time as the voting machines did.”

Rantz said Thursday about critics of hand-counting ballots: “The first irony is that they criticize the accuracy of it. Yet every state I’m aware of, when they use machines to tabulate results, they require hand-counting of some sort afterwards to prove the machines are accurate.”

Rantz also said hand-counting saves time and money, gives same-day results, and is more transparent and has more security than using machines.

She wrote a nearly 300-page manual titled “Missouri Elections: Return to Hand Counting,” explaining how to conduct elections by hand-counting ballots.

Rantz said that Osage County has less than 10,000 registered voters and the April municipal election had under 1,800 ballots.

Despite people saying that only small counties can do hand-counting, Rantz said that across the country, the average polling place gets 600 ballots on election night.

With the conservative estimate of counting 50 ballots an hour, it would take 12 hours for one counting team of four people – two Democrats and two Republicans – to count 600 ballots.

In St. Charles County, Mo., which Rantz said has 290,000 registered voters, there are 120 polling places.

In the elections in which more people vote, such as presidential races, more teams of four can be added, if necessary, at polling places that receive more than 600 ballots on election night, she also said.

States have different laws regarding whether counties are allowed to hand-count their elections, Rantz said. While county clerks in Missouri are allowed to make decisions regarding issues such as hand-counting elections, in Louisiana, the secretary of state makes decisions for the parishes.

Rantz also said on Steve Bannon’s War Room on Real America’s Voice a month ago that the cost for hand-counting isn’t as exorbitant as has been portrayed.

“I think everything that’s being said right now where hand-counting costs so much more money than using machines is just being pushed out to discourage counties from making the change or even looking at the change,” she said.

Rantz also argued that when counties estimate costs, they don’t consider the offset costs of not using machines.

She also said that if Shasta County implemented the same model as Osage for hand-counting, it would be about $100,000 in additional labor costs for a presidential election, not the clerk’s estimate of over a million dollars.

In Nevada, Nye County added hand counting for the 2022 midterm elections to its machine tabulation of ballots and found it to be more accurate than the machines.

In January, a Cleburne County, Ark., quorum court passed a binding resolution requiring all future elections to be conducted with paper ballots and hand-counted.

– – –

Natalia Mittelstadt graduated from Regent University with Bachelor of Arts degrees in Communication Studies and Government.

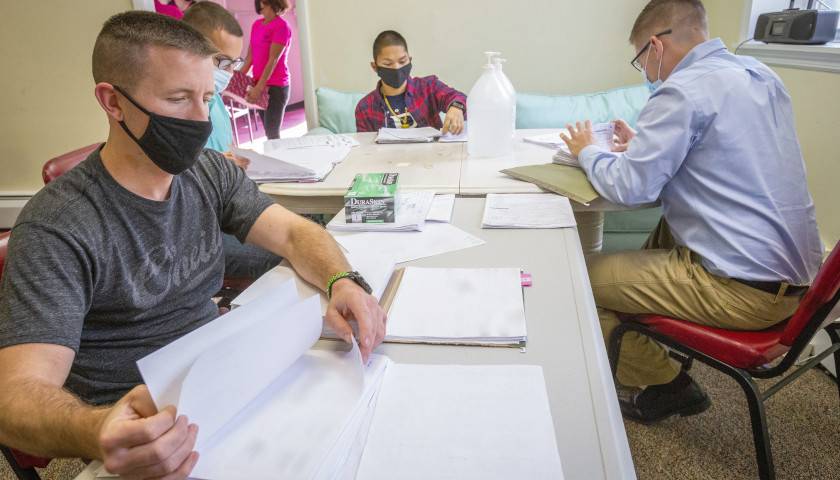

Photo “Counting Ballots” by New Jersey National Guard.